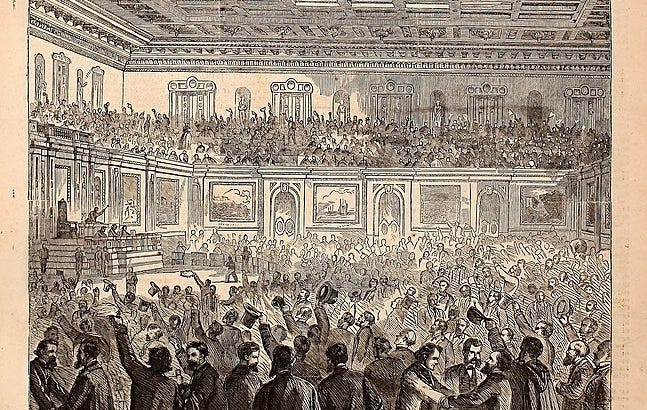

Passage of the Thirteen Amendment, US. House of Representatives

Today is a holiday for which I have mixed emotions. There is social pressure to celebrate freedom. And who could quarrel with the end of American slavery? Not I. I am also a respecter of American history. The more I think about this holiday, this Juneteenth, the more the whole thing seemed contrived. My opinion is seldom heard in the public square. I try to see the fog as a writer. The fog loses power as one turns on the power of discernment. So, rather than care about how others perceive my position, I will express my misgivings. First, I will identify the imperfect muddle. Second, I will offer a preliminary defense of the imperfect muddle. Finally, I will conclude with the wages of unexamined celebration in an age of lost memory.

An Imperfect Muddle.

We associate Juneteenth with freedom for American slaves. The association is a muddle, an imperfect muddle at that. According to the ones who created this ode to freedom, we are to celebrate the end of slavery in the United States. But why June 19 of all days on the calendar? Well, on June 19, 1865 and so the tale is told, “Major General Gordon Granger ordered the final enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas at the end of the American Civil War.” Let’s assume the tale is true. I have no reason to question the credibility of the claim.

What I do question is the ending date of slavery. Because the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18, 1865. This is the date when our U.S. Constitution eradicated slavery. As a matter of logic, shouldn’t we celebrate the date our Constitution became a beacon of freedom under the law?

Celebrating June 19, 1865 and the conduct of a lone Union Major General down in Galveston, Texas was not how most black Americans experienced freedom. Most black Americans experienced the flush of freedom under the gaze of a Union soldier on horseback. That is the moment of freedom for slaves in American history. We should celebrate this moment. The Manuscript and Freedom

The ignorance about history between June 19, 1865 and December 6, 1865 unsettles me. Tens of thousands of slaves remained in bondage on farms and plantations in Kentucky and Delaware during these six months. Who were these tens of thousands of slaves for whom Juneteenth was meaningless?

Think about it as we celebrate Juneteenth today.

In Delaware, there was David Roberts (also known as Logy). Roberts resided in Somerset County, Delaware and was owned by Edward Long. We celebrate June 19 as a date of freedom which mocks the life experience of Roberts. Roberts was freed in Delaware on July 18, 1865, the most important date of freedom in his life. Not June 19, 1865 but July 18, 1865.

There was another Delaware slave, Samuel Burris. Did you know the authorities arrested Burris in January 1847 for the crime of helping runaways? It is true. This supporter of the Underground Railroad gained his own freedom upon ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment on December 6, 1865.

Roberts and Burris were just two of 1,000 to 1,200 slaves in Delaware between June 19, 1865 and December 6, 1865. Source: Chat GPT-4

After the ballyhooed date of June 19, 1865, the number of enslaved persons remained even larger in Kentucky. Estimates range from 40,000 to 65,000 slaves who remained slaves despite the pleasant words of Major General Granger in far away Galveston, Texas. Somehow, it feels wrong to celebrate a date for freedom when 40,000 to 65,000 humans remained enslaved pursuant to the U.S. Constitution.

Wouldn’t it be more respectful to these souls to celebrate their freedom under the 13th Amendment to the Constitution?

On the flip side of Delaware and Kentucky are the lives of 500,000 black people who found freedom by hook or by crook before Juneteenth. Think of the end of American slavery as a rolling admissions into the university of freedom. There were multiple pathways to freedom which a celebration of Juneteenth diminishes. My great great grandfather’s brother, Smith Twyman, strolled off the Madison County place during the Civil War, joined the U.S. Colored Troops and fought for freedom. Juneteenth did not mark his day of freedom.

My distant ancestor, James Twyman (1781 - 1849), manumitted 37 slaves by will, gave them provisions, money and an armed escort out of Virginia to Burlington, Ohio. For these 37 people and their descendants (including my cousin Jimmy Smith) to this day, the momentous day of freedom was the reading of the will in 1849. What does Juneteenth mean for the descendants of the Burlington 37? Does Juneteenth resonate as much in Burlington, Ohio as for descendants of slaves in Galveston, Texas? My point is freedom was rolling admissions. Every family has an individual experience of freedom.

There are other examples out of 500,000 instances to support a rolling admissions view of freedom. “For example, consider the case of Venture. Venture was captured at the age of eight from his native country, Guinea, and brought to Rhode Island. At the age of nine, the slave master assigned Venture the work task of cording wood which Venture became proficient at over time. Venture was around twenty two years old when he married his wife, Meg, a slave. Venture worked cording wood, saved a portion of his earnings and was able to purchase his freedom. Once free by the hand of his own enterprise, Venture continued cording wood and saving his earnings until, one day, he was able to purchase the freedom of his wife and two sons.

But for the skill of cording wood and his earnings therein, the entire family might have remained slaves — Venture, Meg, the two sons. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/venture/venture.html”

The year of 1846 holds special significance for my wife’s family. It was in 1846 that Edward L. Rainey used his savings from barbering to purchase his freedom and the freedom of his family. Juneteenth was nearly thirty years off into the future. What was the meaning of Juneteenth in Galveston, Texas for Rainey in Georgetown, South Carolina, an entrepreneur, real estate investor, and free black barber? I wonder.

Here’s another example of rolling admissions into freedom. This individual story is from Nashville, Tennessee, the story of William Napier of Nashville, Tennessee. “As a slave, William conducted his father’s business on his own. Once free, Williams transferred those business management skills to ownership of a livery stable business.” What was the meaning of Juneteenth for Napier in Nashville?

Here’s another perspective on freedom as rolling admissions from Georgia. “Another example of leveraged skills during slavery would be James M. Simms. Simms was one of the first black lawyers in Georgia. Born a slave, Simms worked as a carpenter. He used his earnings to save money for his freedom. In 1857, Simms purchased his freedom for $740. Those dollars were acquired due to work as a carpenter.” Notably, it was the ratification vote of the all-white Georgia state legislature that moved the 13th Amendment over the finish line. What was the meaning of Juneteenth for Simms in Georgia?

Let’s move up North to Massachusetts and another example of a rolling admissions into freedom. “Another example would be the case of Cumono Morris. Cumono was a slave in Ipswich, Massachusetts in 1750. He received invaluable training as a carpenter. As a result, he helped to build the town’s first church. A street in town is named after Cumono. Those carpentry skills were available to Cumono during his life as a free man. His grandson, Robert Morris, Sr., would become the second black lawyer in American history.”

These instances of individual moments of freedom are lost to memory as we amplify the random words of one Major General in a distant place far from the heart of the South and the North. The individual story of freedom is overwhelmed with a collective narrative that freedom equals June 19, 1865.

Once again, humans live unexamined lives. The details of freedom prove too much for many.

A Preliminary Defense.

Having set forth the case for how celebration of Juneteenth is an imperfect muddle, Juneteenth (A Refrain), is there a preliminary defense for celebration of Juneteenth? I believe there is.

First, the concept of freedom from bondage renewed the American soul. New life was breathed into the words in the Declaration of Independence. It is well that we should commemorate freedom with a federal holiday.

Second, at least the Union solider plays a bit part in the celebratory narrative. The narrative could be worst and create a fiction that the slaves freed themselves! The Thirteen Amendment was an all-white production from introduction of the bill on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives to its ratification by twenty-seven states. Delaware and Kentucky rejected ratification of the amendment. No surprise there. They wanted to keep slavery going and going. Juneteenth? What is that, thought legislators in Dover, Delaware and Frankfurt, Kentucky. No black man or woman anywhere participated in the 13th Amendment. The 13th Amendment was an all-white production from start to finish. These legislators, federal and state, are the unsung heroes of freedom this day, I would suggest.

Depends how one looks at it.

For those who would suggest the 13th Amendment has less credibility as an all-white production, I say would you rather have slavery continued on farms and plantations in Delaware and Kentucky? Are you not as excited about the 13th Amendment because there are no black actors in this narrative of freedom? A pleasing narrative does not matter. It is truth and reality that matters.

Having said that, take comfort, those who can only care about American history if blacks are on stage. Guess who was on stage in a powerful way that day when the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 13th Amendment? A pioneer black lawyer!!!:

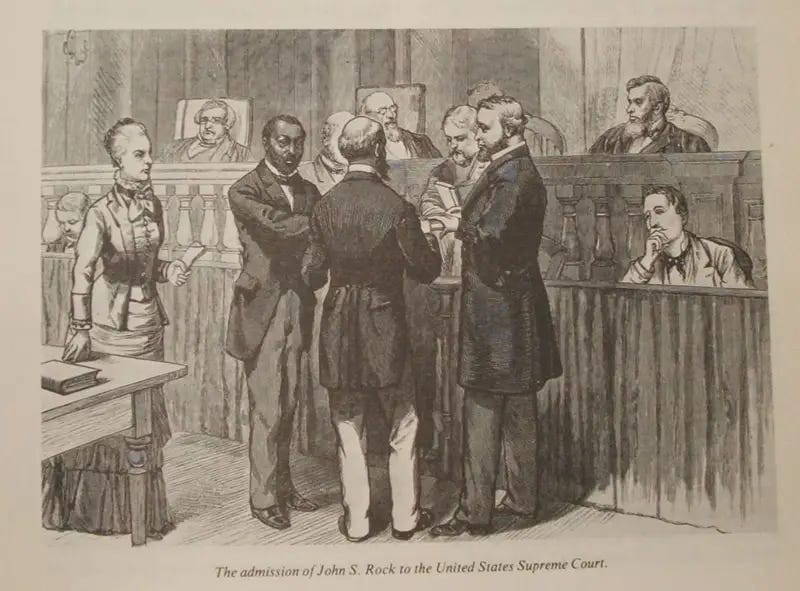

“Attorney John S. Rock made history by becoming the first Black man admitted to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court—and on that same day, he became the first Black person to appear on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

📅 Date:

February 1, 1865

This event occurred just hours before the House of Representatives passed the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery. His presence was both symbolically and historically powerful: a free Black attorney standing on the House floor as Congress prepared to end slavery nationwide.” Attorney (and Doctor) Rock received a personal escort unto the floor of the U.S. House by the Sergeant-at-Arms…a rare honor at the time for anyone let alone a Black man.”

Imagine if we taught real, genuine and authentic American history in schools and universities. Rock also coined the phrase Black is Beautiful which adds to the moment behind passage of the 13th Amendment.

Third, a hyperfocus on a random reading of a document by a random Major General one random day in a random Texas town may cause serious historians to question the full history of Juneteenth and whether the Thirteenth Amendment has been unjustly discounted and forgotten in the public square. There was a time in the late 1800s when blacks and whites poured into the streets and celebrated ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

How far we have come, or not.

Conclusion: I find myself in a mood this holiday season. I can muster up a preliminary defense of an imperfect muddle but little more. I think about Roberts and Burris in Delaware. I think about the 40,000 slaves in Kentucky for whom the Major General’s words in Galveston were meaningless.

Why are we celebrating a day of freedom again when slavery remained the law in Somerset, Delaware and Lexington, Kentucky?

[Kentucky Slavery: Lewis Garrard Clark recounts the moment when his mother—Letitia Campbell, a woman of mixed ancestry—begged on her knees before her enslaver not to sell away her children:

“She fell down before him on her knees, clasped his knees with her arms, and implored him, in the name of God and her Savior, not to sell her children—her babies. But he cursed her and kicked her away.”

This moment—a mother on her knees, a man of her own blood cursing her, the sale of her children imminent—is among the most searing representations of slavery’s cruelty in Kentucky. Clarke’s mother was the enslaved half-sister of her enslaver.]

It is hard to celebrate the emancipation of some in Galveston, Texas when tens of thousands of slave mothers remained vulnerable to sale of slave children in Delaware and Kentucky. Maybe, we should celebrate ratification of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865. A little inclusion goes a long way/smile.

The Rest of the Story of Freedom: James Twyman (1781 - 1849) and His Trust Fund