[Note: In the spirit of the American Dream, the following essay recounts the best in our American past. We are free to choose our destiny. We must choose well. I drafted the essay on April 19, 2006.]

Chapter 1

Money

I played the piano.

I had the long, graceful fingers of a piano player. Even as a sixth-grader, my fingers spanned an octave and a half on the keyboard. Dad would unlock the Church door and I would rush to the nearest room with a serviceable piano, flip through the pages of a Hymnal until I found just the right inspiring song, and go at it. I played and played for hours, reveling in the sounds of the music, experimenting with different octaves, pacing myself so that the tones of gospel and spiritual music moved me. And within the blink of an eye, I would move into Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring by Johann Sebastian Bach, The Messiah by George Handel or Minuet to a Symphony in C by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. I didn’t discriminate. Being moved by the music was the goal.

I was in love, and did not know it.

I grew older and, with age, more set in my ways. As high school approached, I burrowed myself into linear thinking. “I wanted to become President of the United States, so I had to win such and such offices along the way.” “Harvard had graduated more Presidents than any other college, so I would need a Harvard degree.” “Most Virginia politicians were attorneys, so becoming a lawyer would be how I would make a living.” I loved grade school politics. I had an enviable track record of being undefeated for five straight years in junior high and high school. That I hated social gatherings did not matter. That I found refuge and solace in the company of books gave me no pause in my Oval Office aspirations. The odd teacher might compliment my writing. I paid her no mind. Another iterant instructor urged me to consider an acting career, an affirming venue for the introverted and the feeling personality to shine. I did not listen. I had a goal, a noble goal, and years of accomplishment to fuel my self-confidence.

Then college happened.

I ran for office. I reached into my old bag of tricks. I gave an eloquent oration from the heart with the intent of touching the listener. The ability to summon up the verbal muse had been within me for as long as I could remember. I could turn it on and off, an understandable trait for this nephew of several ministers. As a six-year-old, I would preach at nights in the kitchen while an adult pastor preached the word over the radio. I won the election and, at the same time, decided politics was not for me.

I considered myself unattractive. I could not bear the idea of my face on hundreds of posters across campus in future campaigns. I had self-esteem issues. And so my dreams of politics died a stillborn death.

You might think I gave up on law school too. You would be wrong.

I became a preppy at the University of Virginia (UVA). I learned the dress of the Upper Middle Class. A gentleman wears Khakis and buttoned-down, 100% Oxford cloth, white shirts. Topsiders or penny loafers with a blue blazer finished the look. I learned the enunciation and pronunciation of the Southern Elite, although I gained a heavy dose of New Jersey/New York speech from my Jewish roommates. With these lessons came the hunger for money to support my habit. Shopping at Brooks Brothers is not cheap. My goal did not change. I still desired a Harvard Law School (HLS) degree but my motivation changed.

I now wanted money.

The impetus behind affirmative action remained fresh on the heels of the recent Bakke decision. To their credit, UVA administrators favored HLS for their promising black students. I cannot recall a single black student between 1979-83 who chose Yale or Stanford over Harvard Law. I learned about Robert Branson, Jackie Stone, Jimmy Saunders, Leroy Hassell, Marvin Bagwell, Samuel Paschall, and a host of other black alumni before me whom had flocked to Cambridge.

I wanted to be in that number.

What sealed the deal for me was an article in The Washington Post Magazine on Sunday, January 4, 1981. Titled The Black Elite, the article, written by reporter Juan Williams, surveyed the ranks of achieving African-Americans in D.C. That Williams invested so much focus on the black alumni of HLS impressed me. Williams led the piece with a quote from Stephanie Phillips who was then an associate at Arnold and Porter, one of the elite law firms in Washington. The piece profiled Vincent Cohen, partner at Hogan and Hartson, as a member of the burgeoning professional elite. I wanted their bulging salaries and HLS seemed to be the well-traveled route.

So, I became fixated on HLS.

With the cunning of a chess player, I loaded up on history courses. I rocked in history. I had always been at the top of my class in history. I had scored my highest achievement test score in history. History offered the best route for A grades.

By a quirk of good fortune, UVA invited me to be an Echols Scholar. The Echols Scholars program suited entering students who had shown a superior maturity in high school. The program allowed students total freedom in designing their academic program during their four years at the University. The conscientious Echols Scholar selected a strong blend of courses from various disciplines. After all, isn’t that the point of a well-rounded liberal arts education?

I had other goals in mind.

The History Special Scholars program had recently graduated Branson and launched him on his way to HLS. I learned through the grapevine, and was not dissuaded of my belief by Dean Charles Vandersee. Well, if the History Special Scholars program worked for Branson, it would work for me.

I implemented my strategy. I enrolled in the History Special Scholars program, just like Branson. The program was challenging. We had to write an essay once a week. But I found that I had a gift for research and writing. I worked hard and spent many late nights at the Medical School library cranking out critical essays. During those years, I would often be one of the last students to leave the library. Just the memory of those late nights brings back the smell of the medical school corridors, the quiet of midnight hallways, the dream of making it to HLS some day. Those dreams sustained me at 2:00 in the morning as nothing else could.

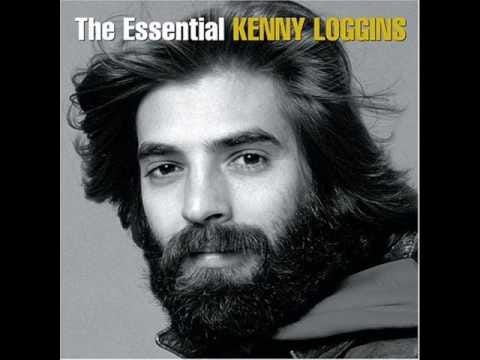

That the History department nominated me for Outstanding History Student bore testament to my mission in life. I recall humming to myself late at night “This is It” from the Kenny Loggins’ Album Keep the Fire. That song inspired me much as a starry night inspired Vincent Van Gogh to capture feeling on canvas.

Dean Vandersee saw the earnestness in me. He knew that, like the cadet in An Officer and A Gentleman, I had no place to go. I had convinced myself that HLS stood between me and a brighter tomorrow. He knew my story. He had read my personal essay in my college application where I wrote that “I did not smoke, drink, or curse.” How my life story must have tugged at his heart. I worked two jobs every summer to pay for my living expenses. I had the persistence of a Thomas Edison, the faith of an activist, the resolve of a self-made student.

I convinced him of my hidden talent. He considered all that I said. With a demeanor befitting an English professor, he agreed to write my recommendation for law school. I had made my case.

I am sure he sang my praises. There was much to praise. Could I write well? I thought so. Could I retain encyclopedic knowledge about obscure facts from the past? You bet. Should I have gone to law school? No.

If the Dean had done some investigating, he would have found that I had enrolled in Logic 101 and dropped the course very late in the semester. Why did I drop the course? Because I stood to receive a lousy grade, that’s why.

What would I do if I didn’t get into Harvard’s Law School? I had no idea. Lineal thinking had trapped me. I had no Plan B. If I had examined my talents, gifts, and interests, the answer was right under my nose. History. History is where I shined, shined so much that I willed myself into nomination for Outstanding History Student at UVA. Graduate school in history called for me, and I chose another mistress, the profession of law.

To keep my American dream alive, I channeled my energies into my personal essay. I would write the essay of a lifetime. My personal essay had propelled me into the Echols Scholar program as a freshman. Surely, those writing skills would do the trick with law school as well. If anything, my writing skills had been honed by two years of immersion in the History Special Scholars program, an incubator for critical writing and scholarship.

I wrote a draft. I rewrote it to add energy. I read it over and trimmed down the adverbs, gutting out passive voice with fanaticism. And then I rewrote the essay again for style and rhythm so as to create a vivid, continuous dream in the mind of the reader. Did I stop? No. I revised again and again, laboring over that essay as if my life depended upon it. I enlisted Dean Robert L. Kellogg of the College of Arts and Sciences to critique my essay. Nothing would be left to chance. I spent minutes debating the merit of each phrase, each clause. Altogether, I revised my essay twelve times before sending it out with my application to the HLS admissions office. And hedging my bets, I submitted simultaneous submissions to nine other law schools as well.

On February 9, 1983, I received a fat letter in the mailbox from the admissions committee at Harvard Law School. I read the first words “we are pleased to offer you a seat in the Class of 1986….” I jumped for joy. I hooped. I hollered. I ran screaming through the Lambert Field dormitories like a madman.

My American dream had come true. And so would my nightmare.

*****

Why do students go to law school?

Students go to law school for many reasons. Most students attend law school for the money. A recent National Jurist article proclaimed that law students could now anticipate starting salaries of $135,000 at major law firms. I read the article with disgust. Students with debt loads in the six-figures will think long and hard before passing up those types of salaries. But the injury, the harm, of these obscene (if that is not too strong a word) articles lie in the fine print. The articles feature freshly scrubbed associates who drone on about the “challenging work” and “opportunity for training” when, in fact, it’s all about the money if you are twenty-four years old and in debt. At least, Donald Trump in The Apprentice is honest.

Just as there are child predators on the internet, hyped accounts of high salaries prey on the vulnerable, the budding wordsmith who can see no other sure way to make a lot of money with a History or English degree. Imagine that you came to college with no clear direction, no discernable calling in life. You are smart and do well with words. You look around and you are unimpressed with a young professor’s house. Or, you hear the history graduate students ranting about the dismal jobs posted on the Department Bulletin Board. And then, one day, you’re studying at the law school. You pick up a National Jurist to read during lunch and you see that real people are smiling back at you from the magazine pages with $135,000 salaries in hand, starting salaries at that!

What would the reasonable, gifted and talented student think?

If one wants to make money, one should attend business school or go into business. The pursuit of profit is at the core of entrepreneurial activity. Even wealthy lawyers have, in many cases, acquired their assets outside the narrow realm of law practice. Reginald Lewis, for example, graduated from Harvard Law School. But Lewis was a natural-born entrepreneur. He had created a series of business ventures while a youngster. He had a head for business. One gets the impression that his stint at a major New York law firm was a way station to his ultimate calling, that of acquiring multi-million dollar businesses in leveraged by-outs.

When Lewis died, Fortune valued his estate at $340 million. No practicing attorney from Harvard Law ever acquired $340 million from the mere practice of law.

Kenneth Chenault earned a Harvard Law degree and drifted to a law firm. But the fit was not right. He found his way to American Express, his true calling, and excelled beyond anyone’s expectations. Today, Chenault presides over American Express as CEO. A gifted and talented businessman, Chenault would not have risen to the heights of a leading New York law firm. His passions led to tough-minded risk taking, a character welcomed in a multinational conglomerate where results can be quantified but lethal as an attorney in a risk-adverse firm setting.

Today, Chenault is worth $20 million. He is one of the wealthiest African-Americans in the country. He would never in 10 lifetimes have acquired those assets as a practicing attorney.

Even being a college dropout is no bar to great riches. Bill Gates is the wealthiest person in the world. His net worth is estimated at $50 billion as of March 2006. Gates dropped out of Harvard during his third year to pursue a career in software development. If you want to die with stupendous assets, law school is not the tried and true way. If you are a successful attorney, you can live a comfortable upper middle class lifestyle. But having a high income is not guarantee of a high net worth, a point made well in The Millionaire Next World by Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko.

If you want to make money, then become a maker of money. Law school is a detour, not the way to accumulation of a fortune. Read Lewis’ autobiography and you will see the practice of law stifle the spirit of a destined empire builder. Research Chenault’s angst after his law degree and you will see a young star in search of his destiny.

A strong argument can be made that higher education is irrelevant to the grabbing of assets. My own Uncle James Scott Twyman became one of the wealthiest African-Americans in terms of net worth. He owned about 16 properties at the time of his death. And yet he had a second or third-grade education. Bill Gates, the wealthiest man in the world, is a college dropout. Paul Gardner Allen, worth $20 billion, is a dropout from Washington State University. Michael Dell, worth $14.2 billion, is a drop out from the University of Texas at Austin. The drive to create a business was so strong for Dell that he began a company in his dorm room before deciding that school was not cost efficient. Larry Ellison, worth $13.7 billion, is a University of Illinois drop out. Steven A. Ballmer, worth $12.6 billion, dropped out of Stanford’s M.B.A. program to join his Harvard classmate (and dropout) Bill Gates. Carl Icahn, worth $7.6 billion, is a New York University medical school dropout, jumping ship after 2 years.

If your goal is to acquire a fortune, there are other routes, paths that do not require the loss of three years in law school classrooms.

Suppose you decide that a fortune is not your goal. Instead, you want to earn enough money to live well, have a nice house, and take fine vacations. It is true that a career in a law firm can provide these “satisfactions.” A life in the law seems to guarantee these upper-middle class aspirations.

Well, not really.

Left unsaid when starting salaries of $135,000 are hyped is the attribution rate. Even when I left law school in 1986, the door was closing on upward mobility in big firms. At a place like Cravath, Swaine and Moore, perhaps sixty-four newly minted associates might enter the first-year class. After ten years, no associates might make partner. What happened to these brightest of the best minds? Law firms are built on a pyramid system. Associates are gangs of fresh lawyers put to work generating billable hours that profit partners at the top. But, increasingly as associates step up the career ladder in firms, they become more and more expensive for the firm to retain. The lucky few are mentored by partners. They develop relationships with clients. They are promoted to partner because they are seen as partnership material, capable of becoming rainmakers. The great many do not develop these relationships and are asked to leave the firm.

Some find other firms to work at and maintain their high salaries for the short-run. But absent a proven rainmaking talent, you will not make partner at this firm or at the next firm. After 5-7 years of being out of law school, fewer and fewer firms will hire you. You are too expensive. And so, some senior associates scramble to find government work with some obscure agency like the Postal Service or the Division of Motors Vehicles that will hire them. The fortunate ones work with federal agencies that have stable offices. Others might ply their trade with the U. S. Department of Justice, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, the Attorney General’s Office or maybe the District Attorneys’ Office. None of these employers of last resort pay high salaries.

The illusion of 6-figure work turns into a mid-career reality of earning $95,000 one day, if you’re lucky. If you think I exaggerate to make the point, read the account of Lawrence Mungin in The Good Black by Paul M. Barrett. Mungin expected the good life as a lawyer. And he earned the hyped salaries at his first firm job. And his second firm job. By the time, he migrated to his third firm, he was long in the tooth career-wise for an associate. Either he would make partner or he would be tossed out in the marketplace to fend for himself. What happened? Mungin dropped from making around $100,000 a year to about $15 an hour as a temp attorney when he left the firm. That reality is the nightmare of every senior associate who doesn’t make partner at a big deal firm. And the odds are against lawyers making partner at big deal firms.

If your goal is the good life as a lawyer, the odds are against you. You will think you are different. You will think you can out compete your classmates. You are wrong. Most big firm partners ranked in the top ten percent of their law graduating class. Ninety percent of the students in law school will find that the hyped riches are beyond their reach. How will you feel in ten years when you are passed over for partner and must scramble to find employment or hang out your own shingle? Therein is not the way to riches.

Money follows your calling. Life is too competitive for the uncompetitive to strike it big. Rather, financial success lies at the intersection of your unique talents and what the world will pay. A review of financial success stories bears out this insight.

Born the son of a physician, this first-born child troubled his father. The boy had no interest in school. The father shipped his son out to Pasadena, California to live with an Uncle. But the change in scenery did not help. He returned to his father’s house in the Bronx and drifted in school. Hoping to find something to interest his son, the father introduced his son to chess. The twelve-year old took to the game with passion. He became a skilled player. The father made an even wiser move on his son’s 13th birthday when he gave his son a camera. The teenager became quite good at photography, selling an unsolicited photograph to Look Magazine of a news vendor the day after President Franklin D. Roosevelt died. He was all of 16 years old.

He failed in every way possible at school. Because he had a meager grade point average of 67, he had no hope of entering college. We would not be surprised if he lived out his life bitter and angry why he didn’t fit in. Every son wants to please his father. What saved the son were his two talents, chess and photography. Using his savings from chess games in Washington Square Park, the young man financed a 16-minute documentary film that appeared in art houses throughout Manhattan. Like St. Paul on the road to Damascus, the young man had an epiphany seeing his work on the wide screen.

He had found his calling. He would make films.

He persuaded his family to loan him money to make two more films. They acquired minor success and were met with critical acclaim. His career really took off when he made Paths of Glory (1957) starring Kirk Douglas. The young filmmaker lost his marriage because of his single-minded determination but not his vision. His later films—Spartacus, Dr. Strangelove Or How I Learned to Love the Bomb, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Eyes Wide Shut—forever cemented his financial future.

That troubled boy, a failure in every way save chess and photography, was Stephen Kubrick.

Another boy grew up in the household of a professor and a painter. He knew he was precocious in poetry. But he decided to learn music. Music offered a surer way for the artistic to earn a living. Year after year, he applied himself with all his heart at mastering musical composition. That he had the honesty after years of effort to admit that he lacked the technique to leave his mark as a musician was the world’s gain. He returned to his natural talent, poetry, and crafted verse. His first three books received critical acclaim.

Yet poetry did not make him rich. Even today, no poet earns his or her living from poetry alone. No one.

This gifted creator of feeling on paper earned his living translating literary works into Russian. And he made a good living at it. He could have lived out his days as a translator, a comfortable existence within the universe of the Stalinist regime.

But he could not.

Something inside of him called to him. Some inner voice said that the story of all that had happened since the Russian Revolution and the fall of the Czar needed to be recorded before truths were lost to memory. The work was dangerous. As a writer, his first obligation was to the truth, an uncomfortable stance in a totalitarian state.

He followed his calling, the urge to create a story that would give meaning to forty years of suffering. He worked on the novel year after year, showing it to close friends as the tale took form. He wrote about the inner beauty of an affair, the outer beauty of a Siberian snowfall. He wrote poetry that made the world weep. And in 1958, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Had he lived in a free society, his royalties would have sustained his children’s children.

The novel was Dr. Zhivago. The middling musician turned poet was Boris Pasternak.

Even if you know your calling, it can be a decade before dividends are reaped. Consider the case of the class cutup from North Hollywood High School. Captain of the football team, he disengaged from school. He earned a 1.75 grade point average, entered a junior community college, and promptly dropped out. He headed into construction work, the employer of last resort for the blue-collar kid not bound for college. He worked long hours and earned a meager income. He had a gift for comedy, however, which his co-workers applauded.

He began going to comedy clubs and doing a few gigs. But the money was sporadic and the work uneven. To pay the bills, he worked under the table and did whatever work presented itself, including boxing. By the time he was thirty, he considered himself a loser. He hammered boards by day to keep his apartment and he performed at night to keep his hopes alive.

One day, he heard on the radio that a local personality, Kimmel, needed a boxing trainer. He called in to the show and offered his services. Kimmel retained his services. The two became friends and Kimmel, noticing his talent, gave him a forum on the radio show. This exposure led to The Loveline on MTV where he served aside Dr. Drew Pinsky. The show made him a celebrity. He went from earning $3,500 to $350,000 in two years’ time.

That man was none other than the American Genius, Adam Carolla. But for toiling away in his God-given calling, Carolla would still be hammering away at construction sites and stressing his next rent payment.

Finding one’s calling and persisting at it is a tried and true way to becoming rich.

And then there is the story of the boy from Menlo Park, New Jersey. He did not learn as well as the other children in school. He was partially deaf. His teachers worried about whether he would ever contribute to society. Once, his mother overheard the principal refer to her cherished son as “addling” or scrambled in the head. His mother would have none of that fatalistic talk, however. She believed in her son. He had clear talents—independence of thought, original vision, steel determination—that needed the right endeavor to flourish. Rote memorization in grade school would not be that place.

His mother took him out of school after three months.

One day, he saved the son of a telegraph owner from certain death underneath the wheels of a roaring locomotive. The father rewarded the hero with a job in the shop where he learned to operate the telegraph. It was a wonderful setting for his interests.

On the verge of starving, he came across a stockbroker’s office where the ticker tape machine was not operating. He jiggled a screw and had the machine back to work in no time. Impressed by his proficiency, the owner offered the tinkerer a job in the broker’s office. The boy continued to invent and would one day be offered $40,000 for an invention.

This boy had discovered his calling. He would eventually earn over 1,000 U.S. patents to his name. He would try and discard over 3,000 filaments before finding the right one to create the incandescent light bulb.

That man with 3 months of formal schooling was Thomas Alva Edison. He would become one of the wealthiest men in America.

The trick is to persist until your calling is in plain view, and then never give up.

His parents gave birth to a stillborn boy. Overcome with grief, they buried their boy. A year later to the day, the mother gave birth to another boy. They named the boy after his deceased brother. Growing up as the son of a minister, the boy came from a somewhat distinguished line of artists and dealers. The boy became very close to a younger brother, Theo, a friendship destined for the history books.

As the boy grew up, he stumbled in his coursework. He lacked people skills, an inability to read people or social situations well. When he tried to become a minister, his fanaticism turned off the flock of worshipers. He also tried to become an art dealer but he lacked the commercial touch, a head for business. He rightly felt like a failure, that he was doomed to muddle from ill-fitting position to ill-fitting position in life.

Someone saw potential in his drawings. They urged to him draw. And in that moment, something clicked for him much like Kubrick felt an epiphany when his 16-minute documentary showed in Village movie houses. The failed minister and art dealer would paint!

He enlisted his dear brother, Theo, in the effort. “Support me, Theo, until I can support myself from my paintings,” he said. And Theo agreed. He began to paint. He painted potato eaters at a dinner table in a haunting fashion. Theo couldn’t sell the painting. He painted a nude woman in despair, an etching that seemed to bring sorrows to life on canvas. Could Theo sell this drawing? There were no takers. He continued to paint at a more rapid rate, bouncing from moments of vivid mania to utter despondency, his use of colors channeling his mood and rendering the mundane sublime and the gray desolate. He painted the night sky with outsized stars of foreboding. In the modern age, his genius would be silencing. For Theo, The Starry Night was another of his brother’s creations that had no market.

What was it in the man that kept him going, steadfast against the headwind of rejections? From what place of utter determination did his faith in his work come? We will never know.

In the final days, he produced a painting a day, all masterpieces. And through it all, Theo could not report good news. At the end, Theo secured one buyer for a painting. By then, it was too late. God’s creation had fallen into a dark place and, in this world, darkness overcame the light. He took his life days later.

The man was Vincent Van Gogh, an artist at one with his calling in life.

Today, his paintings sell for million of dollars.

One can be a failure in the wrong work. But take this failure and place him or her in a field where their talents are extraordinary and one can see the power of one’s ultimate calling. Failures are nothing more than square pegs in round holes.

There was a landowner’s son who didn’t fit in at school. Classmates made fun of his appearance. He came across as a dreadfully serious boy. He failed his university exams. Teachers dismissed him as incapable of learning. Incapable of learning!

He acquired gambling debts. He had troubled sexual relations with women, in part because his brothers had forced him to a brothel for his first sexual experience. Had this troubled dropout lived in the modern era, we would all understand if he developed a drinking problem or a drug habit.

Instead, he wrote. And found his calling. John Gardner has written in On Becoming A Novelist that whether or not a young person can make it as a novelist is a factor of their nature. Does the writer have sensitivity to language? Does the budding wordsmith have a demonic compulsion to write? Has the would be novelist suffered some psychological wound that gives insight into the human condition? Leo Tolstoy fit Gardner’s description like a glove.

His crowing efforts, War and Peace and Anna Karin are regarded as among the most powerful novels of all time. As for money, Tolstoy’s gambling debts liquidated after War and Peace. The royalties from his publications were sufficient to keep him in comfort until his death.

How is a calling different from a job?

When one has a job, one works until the work day is done. One forgets about work until the next work day. There is no joyful compulsion to work around the clock unless one is fated to be a workaholic. When one works at a job, there is no sense that one is in flow, that one loses all sense of time and surroundings. One can imagine Van Gogh painting in all kinds of weather with no regard to the elements or time of day. Similarly, Kubrick invested his all into his work with no conception of a time clock. One acquaintance recalls as many as fifty-six takes on a movie scene until the scene was just right. That is compulsion. That is drive. That is a calling, not a job.

He started from nothing. He willed himself into being an author. Poor and facing a lifetime of labor in the factories, he had to choose between a safe and secure job at the Post Office or an uncertain effort at writing. He chose writing. London resolved to write 1,000 words a day. Every day. It was not easy. He faced rejection after rejection after rejection. And still he wrote. He wrote from the heart, from a steadfast place that would not give up. After 600 rejections, he received an offer. And then another one, and another one. He had mastered the art of publishable writing with the gift of rejection!

Within ten years, Jack London was one of the most famous, and prolific, writers in American literature. He had more money than the Post Office might have ever paid him in a lifetime.

A Los Angeles psychologist began writing at night after the kids were asleep. Publishers rejected his first novel. He rightly assumed that most first novels were not published. And so he began his second novel. No takers. Not dismayed, the writer turned to his third novel. The nights were cold as he wrote into the midnight hour in the garage. No one was forcing him to write. His novels were getting better with practice. He knew it. He could tell. But publishers rejected his third novel. And his fourth. His wife believed in him. He believed in himself. With the ninth novel, he reached the tipping point. That writer was Jonathan Kellerman. Kellerman has now published over twenty-three novels.

That is the destiny of one’s calling.

And there is the poor boy from Maine. Raised by a single mother, he began writing magazine articles for cash. While in college, he wrote a novel but could not find a publisher. He wrote another novel but could not find a publisher. And then he wrote another novel but could not find a publisher. Unable to afford a conventional home, he moved his family into a trailer. And still he wrote. He wrote at night when the wife and the kids were fast asleep. The rejections continued to pour in for his novels. One day, he tossed a half-finished horror story about a teenaged girl into the garbage. His wife plucked it out of the trashcan. She thought it had potential. He no longer believed in the story. She thought differently. At her insistence, he finished the story and submitted it to an editor at Doubleday. The story was Carrie. The writer was Stephen King.

Just because one has a calling does not mean one will strike it rich right out of the starting gate. Even when one is toiling away at their mission in life, disappointments may happen. The trick is to understand that disappointments are an opportunity.

After months of writing and rewriting, he completed his play. He prepared for the big opening night expectant that his hard work would bear fruit. More than anything else in the world, he wanted to know that he could write and write well. He could not bear the first review. A friend gave him the bad news. For a moment, he died a thousand deaths. He thought of everyone he had disappointed. He comforted his friend who was sad for him, “It’s a gift,” he said. “These reviews are a gift.” His friend did not understand, at first. The playwright took those reviews to heart. For eight long years, he worked on a new play. Day and night, he labored. He gave it his all. There was no turning back. And on opening night, Sleepless in Seattle closed to thunderous applause and stupendous reviews.

The writer was Jeff Arch.

Even if one commits to a profession for the security, one’s calling in life doesn’t go away. The calling remains dormant, awaiting the thaw of middle age. Consider the story of a History and English teacher at an English school. This teacher could have ended his days grading papers and marking bluebooks, unknown to the larger world. He was on the path to a good, unsung life.

But he started to write in the mornings before classes. And he liked what he wrote. He wrote during his lunch while colleagues gossiped about campus intrigue. He wrote late at night when the stories spoke to him with an increasing urgency.

He was 35 years old.

He would eventually win awards for his writing, leaving teaching altogether to educate the world with his words. He wrote the screenplay for Dr. Zhivago. And paralyzed from a heart attack and stroke, he found the inner grit to bring to the world one of the top spiritual stories of all time, The Mission, the story of Jesuit priests who chose to remain with their Christian flock in the face of certain death.

This middle-aged teacher who listened to his calling in life was none other than Robert Bolt. Because he found his calling and persevered, Bolt enjoyed prosperity unimaginable in life for a grade school teacher.

Sometimes, life forces us to embrace our calling. We have no choice. Good with words and intelligent, Joe Quirk applied to law school like thousands of other creatives.

But he received a gift. Instead of languishing in the middle or bottom of his class, Quirk failed out of school. Why was his failure a gift? At first, Quirk could not let go of his law school identity. Being a law student had become part of his identity, a misguided attachment before law school and becoming a lawyer was not Quirk’s calling in life. His calling lay elsewhere.

Quirk worked at the cafeteria serving up food to his former classmates. After a while, the shame of facing his failure in the faces of students day after day wore him down. He left law school, crippled financially, and headed out to the Bay Area. Having no place to go, he took babysitting jobs to earn money while he pursued his real interest in writing.

He had failed in a public way, so in a way, he felt freed to become a writer, a profession marked by constant rejection. He wrote and he wrote and he wrote between tending to his charges. Unlike law school where failure has finality, writing rewards perseverance. There are many second chances in writing. Quirk had found his vocation. And he succeeded. After 375 rejections (including a snarky editor’s note from Harper’s to give it a rest), Quirk’s first novel got accepted by Random House. Quirk was on his way as a writer. Failing out of law school had been the gift he needed to embrace his calling. Quirk stood to make more money as a successful novelist than he would ever make as a failed lawyer.

The last story reminds us that profiting from one’s calling is akin to running a marathon. You must stay the course. And if you never give up, if you know in your heart what you are good at, what you thrive at, then success lies over the next hill. Faith will see you through to the finish line.

The daughter of a writer, she had the benefit of seeing a writer’s life up close and personal. Studies show that most writers are not the children of writers, although the reason for this trend is not clear. She went off to Goucher College, a small liberal arts institution back east in Maryland, and failed in every way save one. She wrote well. She excelled in her English classes. In a precocious decision for a 19-year-old, she decided that her calling was to write. Failing college seemed like a waste. London had come to a similar realization when he dropped out of UC Berkeley to write full time.

And so she heeded her calling to write. She worked as a secretary to earn money. She hated the work, work devoid of any lasting meaning. She cried silent tears of despair. Her early writing got poor reviews. Had she made a mistake? She wrote about her father’s death. The reviewers were not impressed. Her editors were downright cold-blooded. Her work needed “revision.” She would drink her sorrows away. She published a third book. The world did not stand at attention. She published a fourth book. Her financial woes remained. Only by her sixth book did she break through and reap the financial benefits of her God-given talent. Today, she is acclaimed as one of the most influential writers of our time. Her work, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, captures the writing process as few books can.

Of course, this college dropout is Anne Lamott. And she is quite prosperous today. But to reach a place of prosperity, Lamott had to soldier on through ill-fitting clerical work, poor reviews, bad novel ideas, heart wrenching “revisions,” and addictions. Success for Lamott was always on the other side of the mountain.

A law job is not a calling.

While a job will provide a paycheck, a paycheck will not provide riches. We know from Rich Dad Poor Dad that employees are limited in their earning potential. Less apparent is the disadvantage of the uncompetitive in the workplace. To be competitive, you must break through the mindset of a job, a 9 to 5 existence. The truly successful know themselves. Like Kubrick, they may be seen as troubled, as a loser, but they have tapped into the one or two God-given talents that they bring to the game of life. Chess and photography would propel Kubrick into a household name. The ability to weather 375 rejections would move Quirk ahead of many of his former law school classmates. The resolve to write 1,000 words a day turned a poor, college dropout into a rich American success story.

If you want money, you must realize your unique talents and gifts. It is the application of your strengths that will give you the competitive edge and make prosperity possible. Choosing law school is wise if it is your calling. But for 90% of students, law school is less a calling than a calling card for a $135,000 job. And ten years after law school, even that calling card has expired.

How do you know your calling?

Dr. Wayne Dyer has written that our calling is where we find inspiration. For you, inspiration might be the joy of converting entrepreneurial risk into capital gain. For others, your moments “in spirit” may have to do with changing a life for the better, one person at a time. I wish I had a better definition for one’s ultimate calling, that I could summon up the words to best describe the sense of alignment when an artist is at one with his work, when the words flow into the writer’s hand from an unknown force, when the inventor, having failed 2,999 times, tries again to invent the light bulb as if trying for the first time, when the young professor teaches with the authority of elders, and when the composer captures a piece of God in his music. I can describe the edges of it, how a calling reveals itself in the lives of the chosen but I fear my efforts are more descriptive than definitive. So be it.

At the funeral of Reginald Lewis, Bill Cosby said that, while born Black and poor in America, Lewis played the hell out of the hand that he was dealt in life.

Whether you are young, middle-aged or old, you have been blessed with talents, gifts differing from the mass of humanity. Think of your unique strengths as your personal playbill for the drama of your life. As the plot of your life unfolds, you can choose to play your strong hand or lead with your weak hand. There is no shame in choosing law school if your strong suit, your calling in life, is logic, fact-retentiveness, and litigiousness. But some readers know their strong cards lay elsewhere, perhaps in a gift for turning a phrase, a passion for enterprise, exceptional recall for the past, whatever. Your calling is your unique hand in the game of your life. Choose your calling and not only will the money follow but you will be aligned with something larger than yourself in this universe.

And that is the truth about who you are.

I really, really love all of your writings and musings and I love the comments too.

I really appreciate Anne's comments.

I have had a rather tumultuous past, as she did, and I am proud of the choices I made to rectify things.

Life is full of ongoing challenges, as we ALL know.

When my sweetheart of 36 years died 20 months ago, I decided that my gratitude for life would bring me the resilience that would bring me more peace and happiness.

Of course serving others is part of this gratitude.

Well, I just got remarried on January 13th and am SO full of gratitude for another man who is helping me become a better person. [and visa versa]

We are both blessed to have family members on both sides who are joyous for us.

So, I now have 4 daughters and another son, along with my 6 sons.

In fact, I just drove one of his daughters to the airport as she heads to Jordan.

She runs an international organization and I am truly blessed to have found another beautiful soul to love and to love me.

Maybe you can tell that my heart is very full today with gratitude to my Heavenly Father.

Very interesting. I was surprised that you brought up Adam Carolla. I’ve listened to him off and on for awhile, and such a bright man. Very impressive for how much he accomplished, especially knowing his childhood, and his lack of interest in school.

This is one of those pieces that is making me think about life, and how we best use it, what it means for each of us, etc. I recently listened to an interview with Mike Rowe, the guy who had that TV program, “Dirty Jobs.” He’s one of the people you talk about, and he’s working hard to help other people find their way, too. I admire the people who make it, and then go on to help others do the same.

I can’t say that all of them have a “calling,” but these are people who have come to the conclusion that there are jobs out there that are going to pay a lot more than the ones they have been dreaming of. One woman wanted to be a doctor. In fact, she wanted to be a surgeon. But when she looked at what it would cost her to get there, she enrolled in a scholarship program though Mr. Rowe’s foundation, and became a welder. She’s so good at it that she’s making $160,000. He talks about the plumbers, electricians, and other jobs that pay exceptionally well, and how many people go on to create their own businesses. In turn, creating more jobs for others.

I would like to think that everyone could do this, but there are often other things that get in the way, and sometimes it’s energy. Some people have a lot of energy, and a lot of desire, but many don’t, and we need those people, too. But, I think what you’re trying to do is talk to the people who think that a particular job is going to be their salvation.

My husband got his MBA when that was an extremely popular field of education. He worked hard, and he was good at his jobs, which mostly had to do with auditing. I think there were plenty of times when he wished he’d gone into something else, but thank goodness, jobs were plentiful, and he was in high demand. We moved around a lot because he was constantly getting calls from head hunters with good paying job offers. In many ways, life was an adventure for both of us.

He was gone a lot, so I was on my own, but it didn’t bother me because I grew up with a dad who traveled, and a very independent mom. He traveled overseas, to Italy, and South Africa. He had several jobs in South America. We were and are, a good team.

We’ve been fortunate, too. He made good money, and we got a decent inheritance from an uncle and my parents. I always had faith in my husband, and I knew life would be good with him, but it has been even better than I ever anticipated. Some of it was luck, but a lot of it was hard work. I can’t say that it was a calling, but it was about seeing opportunity, and taking some chances.

I guess that isn’t very helpful, but it’s another angle on things. Still, it really is wonderful to read about people who have persevered, and found something they loved, were successful at, AND made money doing it!