One day at the firm, I was talking about my interest in Black History with partner Harold Marsh. The law firm Hill, Tucker and Marsh located at 509 North Third Street (an address I will never forget) was located in the heart of Richmond’s answer to “Black Wall Street.” Lawyers, doctors, newspapermen, dentists, preachers, hotel proprietors — all black and all located within a neighborhood known as Jackson Ward. Harold, a no non-sense lawyer, counseled me to drop Black History and major in something of value to our people like economics. We needed black students to major in economics. I replied that history was important nonetheless for a black law firm like Hill, Tucker and Marsh. Who would write the firm’s history one day? He thought about it and said someone needed to write a book about all the firm had done.

=========

Some back story is in order.

I was a college student at the University of Virginia (UVA) and wanted a legal job for the summer. The year was around 1982. I had literally walked up and down Main Street in downtown Richmond, knocking on the doors of about 50 white law firms, resumes in my hand at the ready. No one offered me a paralegal job for the summer, although Hunton and Williams partner John Charles Thomas took time out of his busy litigation practice to talk with me and pontificate on my dreams of Harvard Law School.

I was a nobody off of the street and the first black partner at Virginia’s most prestigious law firm, Hunton and Williams, was giving me the time of day. No job offer but I felt important in the moment.

My hero in the law, Reginald Lewis, once said, never give up. I had the idea I should try Hill, Tucker, and Marsh for a job. Hill, Tucker and Marsh was the most influential black law firm in the state of Virginia. The first black mayor of Richmond, Henry L. Marsh III, was a partner at the firm. Would the firm see something in me? The firm was located in a one-story red brick building across the street from a red brick Third Street Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church. In my known world, red brick buildings were a step up in the world from wood-frame buildings. My great great grandfather and his family attended this church before founding our family AME church in 1871.

I stepped inside the lobby and explained my purpose to the light-skinned receptionist. Partner Jim Benton, a University of Virginia graduate, came out to meet me and took me back to his office. We had a great conversation which turned into a job interview. When my time was up, I was offered a job on the spot.

=========

All of the partners at Hill, Tucker and Marsh took me under their wing. I especially want to remember Harold in this essay. Harold served maybe once or twice a week as a Substitute Judge at the courthouse in Manchester, Southside Richmond. He invited me along to attend his judicial sessions and I was only too happy to tag along. In the car ride from downtown Richmond across the James River to Southside Richmond, Harold would talk about his life, how he was one of the first black students at UVA, his engineering studies, his efforts to install unisex restrooms at the firm which seemed New Age to me at the time, his children destined for UVA and Harvard Medical School, his pro bono and non-profit works in the community. He took an interest in me as we drove to the courthouse. Why was I majoring in Black History again? Who would write the history of the firm one day? My memories are fleeting of the details as we drove along Hull Street towards the courthouse but I remember those drives and being in the presence of a good man.

=========

The firm Hill, Tucker and Marsh began in the year 1942 as Hill, Martin and Robinson. The bread and butter of the firm’s early work was litigation against race segregation in public accommodations and schools. Oliver Hill, first on the letterhead, was a native of my Chesterfield County, Virginia. He graduated in the Howard Law School Class of 1933 second in his class behind Thurgood Marshall. The firm would monopolize civil rights litigation throughout Virginia in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. For example and on May 23, 1951, name partner Spottswood W. Robinson III filed the case Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward in federal district court, asking the court to prevent the county from discriminating against Black students and to declare segregation unconstitutional. This case would be consolidated with the famous Brown v. Board of Education case.

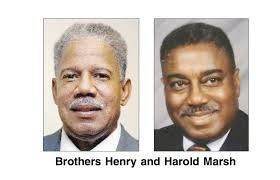

The firm decided involvement in politics was a shrewd strategic way to increase the firm’s influence on behalf of black Richmond. Hill was elected to City Council in 1948, becoming the first black member since Reconstruction. Henry Marsh became the first black Mayor of Richmond in 1977. Later, Marsh would represent the city as State Senator. I once assumed Henry was the name partner before Harold and I set out on our drive along Hull Street to the Manchester courthouse. Harold looked at me and asked, why do you assume Henry is the name partner on the letterhead? Classic Harold. Henry and Harold were brothers.

=========

When we obsess over tragedies like the race riot incident in Tulsa, Oklahoma, it is easy to forget this “Black Wall Street” trauma was not the black enterprise story for most people in the South or the North. Richmond, Virginia offered a clear case of professionals and businessmen creating enduring institutions over the course of a century starting with the first black bank owned by a black woman, Consolidated Bank and Trust where my Dad banked. Hill, Tucker and Marsh claimed Consolidated Bank as a client.

The Golden Age of Hill, Tucker and Marsh passed away for many reasons. First, politicians were eager to appoint more blacks to the bench. If one were a black lawyer at Hill, Tucker and Marsh, one had instant credibility, connections and contacts in the state of Virginia. At least 12 lawyers from the firm would become judges, either federal or state or local. Name partner Robinson would become Chief Judge of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. Benton, the guy who hired me as a paralegal, would become a state appellate judge. Another lawyer became a City Circuit Court judge. Henry was recruited for the federal Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals but Henry preferred the arena of civil rights litigation and politics.

And Harold was serving as a Substitute Judge down across the river in Manchester, Southside Richmond.

When you raid the lawyers of a black law firm for the bench, the bench becomes more integrated but the firm is left bereft of legal talent. The wages of success and political influence.

Young lawyers out of Harvard and the University of Virginia saw more opportunity in the larger world of white law firms. It was more tempting to accept an offer from McGuire Woods Battle and Boothe than Henry’s old law firm. As the 1980s and 1990s turned into the 2000s and 2010s, the best and brightest black lawyers no longer had Hill, Tucker and Marsh on speed dial. In a way, this was progress for the young. But I wonder how Oliver Hill and Henry Marsh viewed future prospects for their vintage black lawyer firm in the early 2000s? Many of these young black lawyers never knew a day of segregation in their lives in public accommodations and schools like I had.

Partners grew old with time. Oliver was 100 when he passed in 2007. I knew Oliver when I was a young paralegal but, even in 1982, time was moving on for the partnership. I know one young lawyer whose rightful inheritance was partnership at the family firm. She left the firm because her interests were elsewhere in life. Another sign of talent drain.

There appeared incompetence in the ranks. A 1,000-lawyer firm can afford an incompetent lawyer or two. For a small aging law firm, an incompetent lawyer can be the kiss of death.

=========

All of these reasons are logical and cerebral. I feel a more emotional incident imposed a wound the firm never recovered from.

I was a law professor in San Diego. The year was 1997. Over the years and on one or two occasions, Henry would tease me, say I should return home. Henry knew better. Once the farm boy sees Paris, he is not returning to Kansas/smile.

One day in the summer, I heard the news from Richmond. A man on parole from California had gunned down my Harold at the intersection of Hull Street and Cowardin Street. Harold was stopped at a stop light on his way back to the firm from service as a Substitute Judge. The doctors pronounced Harold dead an hour and thirty minutes later. A Senseless Killing

How many times had Harold driven me past that intersection when I was a young kid in 1982/1983 with the rest of life ahead of me?

There is no happy ending to this story. Know this tho’ — the murderer will not be remembered. We will remember Harold, and the law firm Hill, Tucker and Marsh. Brother Henry wrote the book so that we would never forget the Golden Age of a prestigious black law firm in the South.

In Memory of Harold Marsh