As we approach Black History Month this year, the question is fairly raised, why study Black American history? I never want to study Black History out of pity or mournful lament. Nor do I want to mindlessly pay homage to an activity that has outlived its purpose and meaning. We should never shy away from the underlying question, why? Have we outgrown Black History? Do we ask of Black History something which can no longer feed our souls? I love Black History but my love doesn’t mean you will love Black History as I do. Was my young writer friend right to be bored with Black History Month? Was my young pre-teen daughter right to question the need for a book Blacks At Harvard? She felt there was nothing special about being black at Harvard, so the book was offensive, problematic.

Has the time past for Black History? Is there no room for black accomplished ancestors anymore? Forgive me readers for my continued belief in study of our past.

I was born in an American past unrecognizable to my cosmopolitan adult children. For me, I believe in the study of Black American history for several reasons. First, abundant knowledge about our racial past means people are less vulnerable to racial manipulation. For example, if one is taught about black acting Governors and members of Congress in the 1870s, one will be less likely to believe black people were mute, deaf and dumb victims in the 1870s. Manipulation works when memories have been stripped of black privileged ancestors.

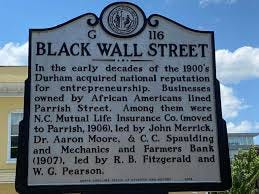

Second, the human condition is nuanced and complex beyond belief. Black history reminds us that each individual engaged the world on his or her own terms. No one was ever an avatar for a race. What have we wrought when students learn about “Black Wall Street” in Tulsa, Oklahoma and not vibrant black centers of enterprise in Durham, North Carolina, Richmond, Virginia or Harlem, New York throughout the 1900s? There is more black history to enterprise than one race riot in one isolated place in Oklahoma. “For much of the 20th century ‘North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company’ was the largest company run by African Americans.”

Allow me to quote at length from Wikipedia:

“The company came to be known as the world's largest African American business in only its first few years and is claimed by its home city of Durham as an important landmark. In the late 1800s and throughout the 1900s, Durham was known as "The Black Wall Street of America" for the progress that African Americans were making within the town. The company's founders, thought to be inspired by North Carolina business tycoon Washington Duke, included John Merrick and Aaron McDuffie Moore, two particularly influential men in Durham's history. North Carolina Mutual and its prosperity brought many good things to Durham's black community, and its founders and organizers were important contributors to social and economic progress in the city and particularly in its African American community.”

How many high school and college students learn about the enduring symbol of black enterprise in Durham as opposed to the race riot in so-called Black Wall Street of Tulsa? A rich infusion of real history brings distortion into clear view.

Third, black American history is American history. We have to reach a place where history is a unified past. Think of it this way. If I spent all of my time studying my Twyman family history, I would be ignoring my history through my Mom. My unified history as a person includes all of my ancestors. Similarly, we should aim to learn American history which is composed of black American history and other histories as well.

The purpose of history is to bring us in touch with our common humanity. The study of black American history should never be to the exclusion of other relevant parts of our history such as white abolitionists, white mentors of pioneer black lawyers, white teachers with the American Missionary Association down South after the Civil War, Jewish investment bankers and financiers of black entrepreneurs, and white professors at historically black colleges and universities. The story of common humanity needs to be remembered in the study of black history.

Finally, unity is our strength. One hears about diversity being our strength but unity is closer to the soul of the American story. Over the coming weeks, these reasons will bring me to the keyboard each night as I remember pioneer black lawyers.

We have to get away from dogma and slogan words. A return to enterprise and the pioneer spirit in American history is in order. Why Pioneer Black Lawyers Matter

Good evening.

Another good post and good argument for history done right; history that illuminates rather than indoctrinates.