So, how did I become Black?

The question seems relevant if I have retired from Blackness. Seems like a fair inquiry for the curious soul. To answer the question, I left my home at noon today and drove down to the Central Library in downtown San Diego. I drove by striking encampments of the homeless. I was blocks from the Padres’ stadium. It had been a few years since I graced this part of town. A number of homeless people were black but my consciousness of Blackness did not derive from homelessness. I never saw a homeless person until I was in law school in 1983. I always fear people will associate Blackness with homelessness since San Diego is around 6% black yet 40% of the homeless (for whatever reason) appear visibly black by American standards.

(I did not see one black homeless person on the tropical island. Not one. Nor did I see anyone of any race panhandling and begging for money on streets. Just an observation. I have no answers.)

=========

I did not become Black when my parents and hospital staff assigned me a race at St. Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. Becoming Black presupposes a consciousness, an awareness. https://archive.org/details/blackcultureblac0030levi I had no race awareness on the day of my birth. Nor did I have a self-awareness of race at the ages of one, two, three, four, five, six, seven or eight. I had an uber awareness of family as I have discussed before in several essays. Family was my known world until the age of six and family/neighbors until the fall of 1969.

Nor did I become Black in a way that mattered over a lifetime upon being called a racial slur for the first time by classmates in the fall of 1969. The prejudiced did not define me and my sense of self over my life. I credit a healthy identity created by my close family. Family influences trumped bigotry from outsiders. Had I taken my clues from the negative in the external world, I would have become Black in a manner alien to my parents and Grandma, uncles and aunts.

As I sat down on the third floor of the central library, I held in my hands the raw material for how I became Black. The moment felt like kneeling before an ancestor’s tombstone at the family church or walking through the halls of one’s elementary school. A part of me came alive in memory. I began to thumb through past issues of Black Enterprise magazine from the years 1972 and 1973.

=========

As opposed to believing delusions that are not true, I wondered about the words in Black Enterprise magazine that entered my brain as a fifth and sixth grader. My Uncle James Scott Twyman wisely left issues of Black Enterprise magazine on the coffee table in Grandma’s living room for the benefit of nephews and nieces. Uncle James Scott never preached enterprise to us. His influence was far more subtle and masterful. As we flipped through Black Enterprise, we would draw our own lessons about life and the way life worked.

Before I continue, I should clearly explain Black Enterprise. Earl G. Graves, Jr. began publishing Black Enterprise in August 1970. The magazine targeted Black Americans who wanted the achievement of economic freedom. The accomplishments of leading blacks in the worlds of business and finance were constantly profiled. More serious than Ebony and Jet, the emphasis was on enterprise, ergo, the name Black Enterprise.

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/black-enterprise-1970/

=========

Before I read the past issues of Black Enterprise, I mapped out a thought experiment. Professor Martin Seligman has written that much insight can be gained from a word cloud analysis. The words one uses can bear upon one’s state of mind. I was curious — did Black Enterprise introduce me to words for understanding the world that one hears in the public square today? I wanted to know.

So, I created a list of sixteen slogan words I oftentimes hear on the airways and in the literature today for understanding one’s self and the world:

Systemic Racism

Institutional Racism

Privilege

Oppression

Oppressor

Oppressed

Marginalized

Intersectionality

Center Blackness

Colonizer

Black Lives Matter

White Fragility

Anti-Racism

Diversity

Equity

Inclusion

=========

The next step I took was to select four issues from my fifth and sixth grade reading experience. I only had two hours for my lonely research, so I chose with care four issues to examine — (1) The Business of Jazz, Black Enterprise, February 1972, (2) Opportunities ‘72: Blacks & Corporations, Black Enterprise, March 1972, (3) Black Lawyers: A Brighter Future?, February 1973, (4) The Nation’s 100 Top Black Businesses, June 1973.

What would I find? Did Black Enterprise use any of the sixteen slogan words I have listed as a way for explaining and presenting the world to me, a little fifth and sixth grader?

The answer is…no. None of the sixteen slogan words appeared in the four issues of Black Enterprise I reviewed.

I did see one reference to “black liberation” but the context was a book review of the Autobiography of Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. If you know Congressman Powell, the use of the phrase “black liberation” made reasonable sense. Powell was known as Mr. Civil Rights during his time in Congress. I did not feel I was being steered or manipulated to understand the world as a black liberationist. There was also a reference to disparities by U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Chairman William H. Grey III. The reference to disparities was reasonable given Chairman Gray’s position. I felt no manipulation.

=========

As I read the issues of Black Enterprise, I remembered precious moments of self-discovery as a kid at Grandma’s house. The Board of Advisors for Black Enterprise were all stand up professionals and leaders — Hon. Julian Bond, Member of the GA House of Representatives; Hon. Edward Brooke, U.S. Senator from Massachusetts; Hon. Shirley Chisholm, NY Representative in Congress; Hon. Charles Evers, Mayor, Fayette, MS; Black Enterprise Publisher Earl Graves; William Hudgins, Vice-Chair of Board of Directors, Freedom National Bank, NY; Thomas A. Johnson, NY Times writer; John Lewis, Former National Chairman of SNCC; Henry Parks, Chairman of Board, H.G. Parks, Inc. (Parks Sausage).

These were people, all Black, whom I learned to revere and respect. The life lesson I divined was to aim high and achieve well. In other words, the best of Blackness lived in these men and woman.

A social justice agenda was not paramount. Just wasn’t.

I reviewed an article about Black Accounting Firms. So typical for Black Enterprise. Readers were to acclaim, and root for, black professionals breaking through racial barriers. I use the word “race pioneers” which is engrained in me as a singular meaning of Blackness.

Allow me to quote Publisher Graves from the Publisher’s Page of the February 1972 issue — “Therefore, when our children read about the Frederick Douglasses of our time, they will be reading a part of history detailing our achievement of economic freedom.” When I first read those words, I was lost in Becoming Black under my Grandma’s roof while my Uncle Scott was buying yet another rental property for fifty cents on the dollar.

Were there troubling things in Black Enterprise? The early 1970s were an awful time for black Americans. Surely, racial horrors and oppressions were present in the pages I read. You may be wondering whether I am sugar coating Black Enterprise.

Well, in the four issues I selected this afternoon for my walk down memory lane, there were jarring moments that I did not remember. For example, I was stunned and depressed by the numerous advertisements from the tobacco industry. Over half of the ads were for cigarettes — Pall Mall, Eve Menthol, Marlboro, L&M, Benson & Hedges, Kool. My Mom smoked cigarettes. My Mom died from cancer.

I leave it to you to decide whether Black Enterprise has blood on its hands.

Black Enterprise put racial prejudice in one’s face. I read a story about thirty-five-year-old Charles Wells. An executive with a major pharmaceutical firm, Wells and his family were the only black family in the neighborhood. Wells “had the best house in the area and…also the biggest car.” The neighborhood was white blue-collar. Wells decided to move from Norwalk, Connecticut back to their old New Jersey suburb outside Philadelphia. Why?

“I spoke to one of my neighbors as I drove by one day and he said, ‘Hello n——-.’”

I do not remember reading this passage at Grandma’s home. If I had read the passage, how might the racial slur have impacted me? Would I have been reluctant to keep reading Black Enterprise? Would I have become alienated from Blackness? These are questions I raise.

For whatever reason, I did not read this shocking story of race prejudice as a youngster.

I do recall reading the ad BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL BUT ITS NOT ENOUGH TO MAKE IT…It takes talent and inspiration — plus a knowledge of what your competition is doing. And there’s no more authoritative source for locating blacks on the move in business than Black Enterprise…BLACK ENTERPRISE For Black Men and Women Who Want to Get Ahead.” Source, Black Enterprise, February 1972, p. 53.

Well, that ad set my young soul on fire. Becoming Black was about getting ahead. Sounds good to me.

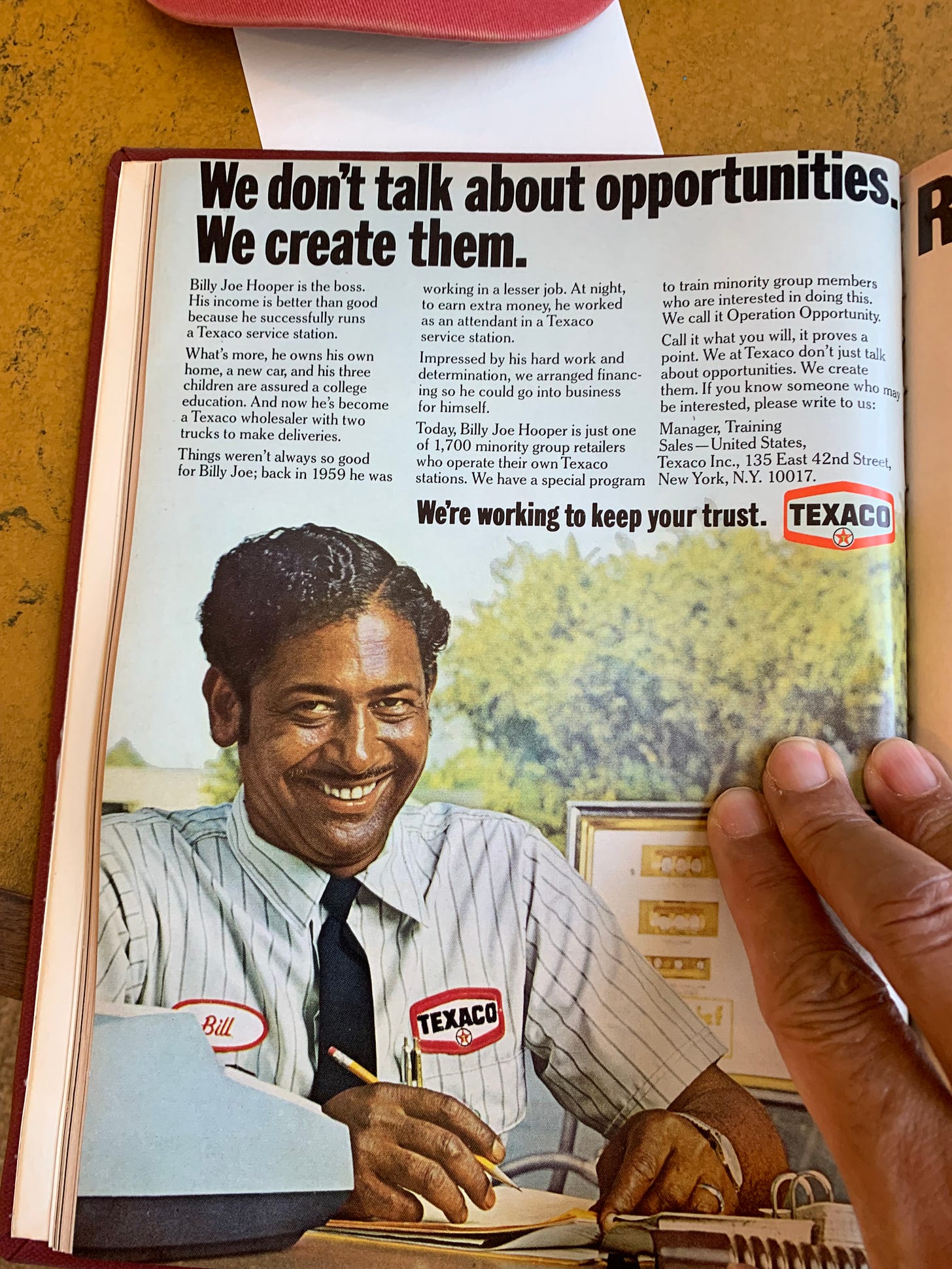

One of my distant Brown cousins on Grandma’s side of the family owned a service station on the Petersburg Turnpike. Ownership of the service station was a source of pride for the extended family. So, the pictures and stories of black service station owners like Billy Joe Hooper resonated deeply with me. Hooper owned his own Texaco service station. He was a home owner with a new car and three kids going to college. In 1959, Hooper was working two jobs. By March of 1972, Hooper was on his way up into the American Dream. I came of a family where men worked two jobs as a given. Very Jamaican/just kidding. The upward mobility in Hooper’s life story echoed the life stories I witnessed among Black dads in Hickory Hill and on Jean Drive in Chester, Virginia.

Source: Ad, Opportunities ‘72: Blacks & Corporations, Black Enterprise, March 1972

With every reading of these stories at Grandma’s house, I was becoming Black.

There is more that came flooding back to me, memories of Becoming Black —

Dear Sir:

I’m delighted to be receiving Black Enterprise. I find it an excellent magazine for my purpose and have recommended its use by my students. It’s much more than a business magazine, and that’s what pleases me most about it. My purpose isn’t just to have students learn about blacks in the business world, but to have students learn about blacks, period. — and as much as possible, in a positive yet believable light. And this is how Black Enterprise reads to me.

Professor Stanley Stark Graduate School of Business Administration Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan

(Source: Letter to the Editor, Black Enterprise, March 1972, p. 10.)

Typical of the psychology defining Blackness was this quote — “…they appear confident of advancement despite the roadblocks…He might also added that they are determined.” Id. at p. 39 (description of mindset of black executives)

In the fourth grade, I decided I would become a lawyer. And Black Enterprise was there to light the pathway of race pioneers in the law. I would read that just 1.5% of lawyers were black. 3,845 out of 325,000 lawyers. The emphasis was on the possible, not the obstacle. Notice how the steadfastness of Ulrich Haynes was treated for readers —

Ulrich Haynes, a black graduate of the Yale Law School of 1956, still keeps his 135 letters of rejection from firms with which he sought employment. Perhaps Mr. Haynes capitalized on being invited out of the profession, for today he is a vice-president of the Cummins Engine Company.” (Source: Black Lawyers: A Brighter Future?, Black Enterprise, February 1973, The Publisher’s Page, p. 6.)

For a young kid in a southern suburb attending a 3.74% black junior high school, these words were bracing. They formed bricks in my sense of self. The words of enterprise and triumph over adversity became me. Today, I am a graduate of Harvard Law School and a former law professor.

I was spared the non-sense Blackness is Oppression. Nothing else matters.

=========

Conclusion: I became black reading the pages of Black Enterprise in my Grandma’s living room. Day after day, my heroes became Publisher John Johnson of Ebony and Jet, Motown founder Berry Gordy, Entrepreneur Percy Sutton, Corporate lawyer Reginald Lewis, and, of course publisher Earl G. Graves, Jr. Imagine a little kid teaching himself that the best virtues of life — Enterprise, Triumph over Adversity, High Aim, Achievement — defined Blackness.

I was self-taught in Blackness under my Grandma’s roof. Black Enterprise was my primer.

Now, you understand why I have retired from a world that defines Blackness As Oppression. Nothing Else Matters.

“Our journey of accomplishment…will end when the majority in America understand that impoverishment can be a state of mind, and not just a physical condition solely assigned to the ‘disadvantaged.’” — Publisher Earl G. Graves, Jr. to his Father, Earl G. Graves, Sr. Black Enterprise, June 1973

A friend recommended this piece and I shall pass it on to others. What we teach, and the expectations we create when children are young are powerful formative influences. I have seen this on the positive side and am seeing it now, at a bit of a distance, in a family that is not setting expectations and a little girl is suffering from that. It is sad to see it happen and understand that her life will not be what it could be.

Just such an important and urgent story to tell-changing paradigms is hard - harder now since the 16 words are like hard cement in the lives of so many for whom this article can create the energy to escape. Hispanic Business Mag did the same for me in the 80’s and 90’s-